From the dawn of civilisation, the snake has been synonymous with various ideological representations of chaos, malevolence, protection and healing in almost every culture across the globe. In Egyptian society the serpent played a magical role within the realms of healing: both apotropaic (turning away harm) and prophylactic (safeguarding from harm). Yet the snake was also conceptualised as an evil entity in the form of Apep who was monstrous and the embodiment of disorder. Consequently, numerous spells were included in texts of tombs to ward off the evil serpents that densely populated the duat or netherworld. The most iconic and popular representation of the snake, however, remains in the narrative of the tragic death of one of Egypt’s most famous queens, Cleopatra VII.

The date was August 12, 30 B.C. and it set in motion one of history’s most epic stories—even providing inspiration for Shakespeare, whose Antony and Cleopatra was first performed in London about 1606. An intriguing story of lust, power, deceit, incest, murder and suicide; ending in one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in history: how did Queen Cleopatra die?

The ancient writers give us a glimpse into Cleopatra’s extraordinary life and psyche concluding with various accounts of her tragic demise. Suicide is the common theme in all the narratives and all concur that two of her handmaidens died with her. Strabo provides the earliest account and is the only source that could have been in Alexandria at the time of her death. He mentions two possibilities; that of the venom of a snake or a poisonous ointment. Galen refers to a belief that she bit herself and poured snake poison into the wound. Dio Cassius states the only marks on her body were slight pricks on her arm implicating a snake as the culprit, which could have been brought to her in a watering jar or among flowers. The most famous account by far, however, remains Plutarch’s and it is his explanation which has managed to survive the test of time.

Plutarch tells us her death was very sudden. A snake was carried into her with figs by an Egyptian peasant, and lay hidden under the leaves in his basket. Cleopatra had given orders that the snake should settle on her without her being aware of it and baring her arm, she held it out to be bitten. He offers an alternative possibility of poison being concealed in a hollow comb she kept in her hair. Interestingly, Plutarch tells us that there were no marks on her body or physical signs of poisoning. The snake was also nowhere to be seen apart from some fresh tracks indicating its earlier presence.

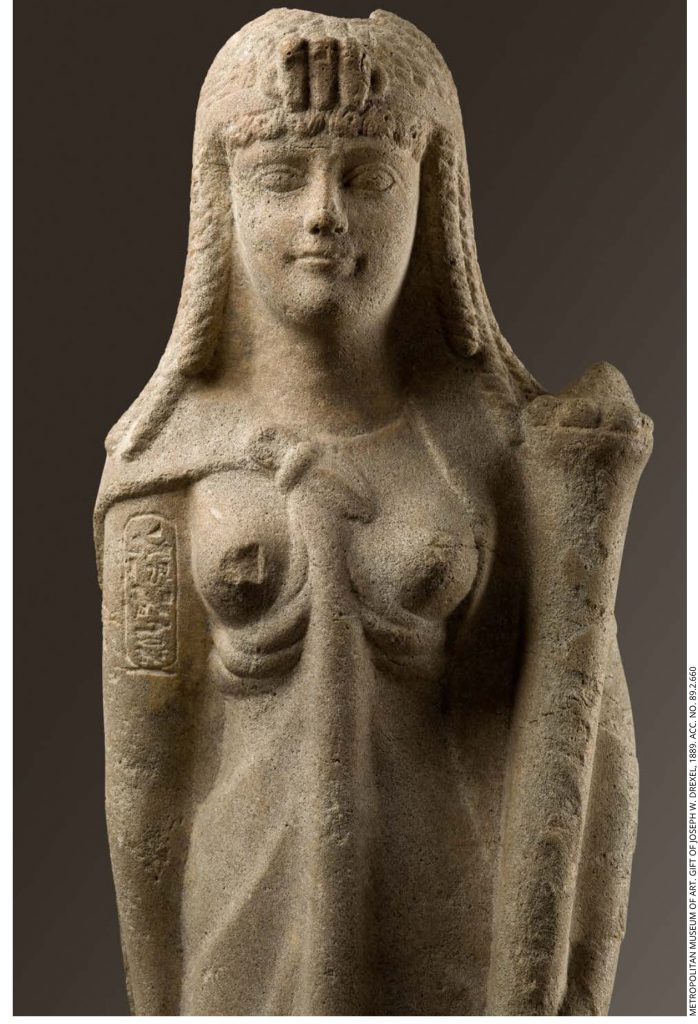

In 2015 academics at the University of Manchester reopened the discussion on Plutarch’s account and argued that the cobra in question would have been too large a species (typically 5-6ft long) for concealment in a basket of figs. Furthermore, herpetologist, Andrew Gray explained that there was just a 10% chance of death since most bites are dry bites that don’t inject venom. So why has the snake story prevailed? Plutarch was not an eyewitness and writes around 150 years after Cleopatra’s death. In order to unravel this mystery we need to take a closer look at the serpent in Egyptian myth, magic and medicine. This is significant because Cleopatra represented herself as the reincarnation of Isis, a goddess of magic and healing and the consort of Osiris.

How plausible is Plutarch’s claim? Cleopatra’s fascination with medicine is documented by some writers and there is even a suggestion she wrote a treatise on cosmetics. Whether or not she actually wrote the treatise is questionable because much of what is stated to be included in it was already available in the Ebers papyrus which predates Cleopatra. Some interest in medicine and cosmetics however, is evident from her lifestyle and her physician Olympus was very much part of her inner circle. Plutarch’s claim of her interest in snake venom is also plausible. What knowledge did the ancient Egyptians have of ophiology though?

The best example of this can be found in the Brooklyn papyrus numbers 47.218.48 and 47.218.85. This artefact is in the Brooklyn Museum and dates to the early Ptolemaic period but the original is thought to be from a much earlier period. The papyrus was a manual for medico-magical practitioners (Serqet priests) who may have been called upon to deal with snake bite victims. The first part of the papyrus lists twenty one snakes although it is thought that it may originally have listed thirty seven. Some identification with snakes of our modern day world was made by the French scholar Serge Sauneron who translated the papyrus into French. John F. Nunn (1996) consulted with Professor Warrell at Oxford regarding identification. In some instances he concurred with Sauneron and in others made a different identification. As a result we have a list of the possible species identified by the ancient Egyptians. These include the spitting cobra, hooded malpolon, black dessert cobra, Persian horned viper, sand boa, puff adder and the Egyptian cobra (Naja Haje) which is implicated in the death of Cleopatra.

To read more : https://www.academia.edu/36915262/An_Examination_of_the_Death_of_Cleopatra_and_the_Serpent_in_Myth_Magic_and_Medicine