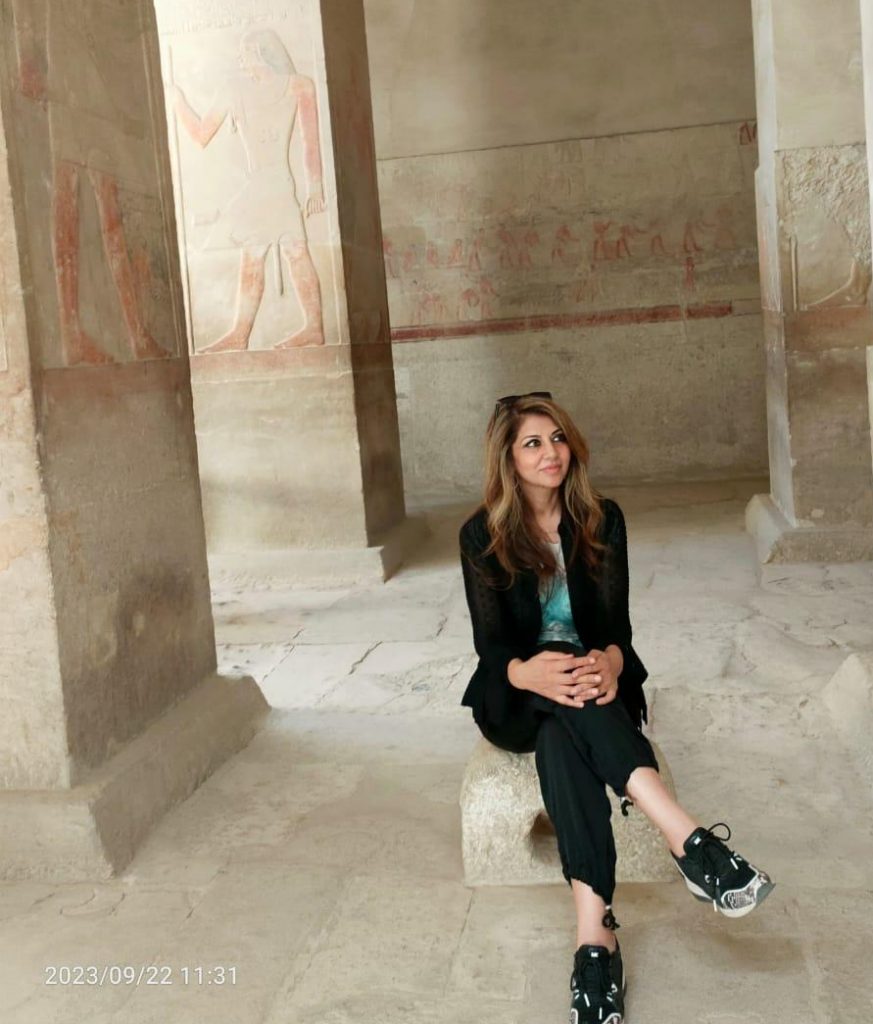

A clip from Hatshepsut HerStory. Full film linked below:

Vital Organs

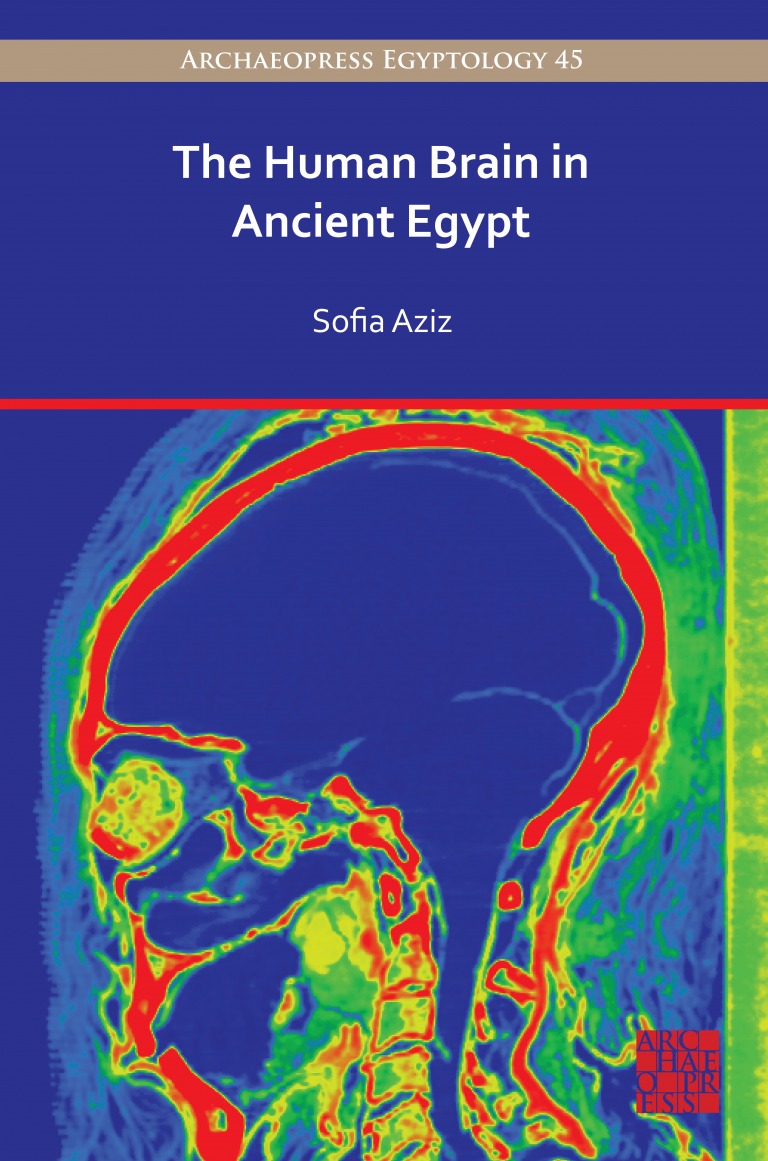

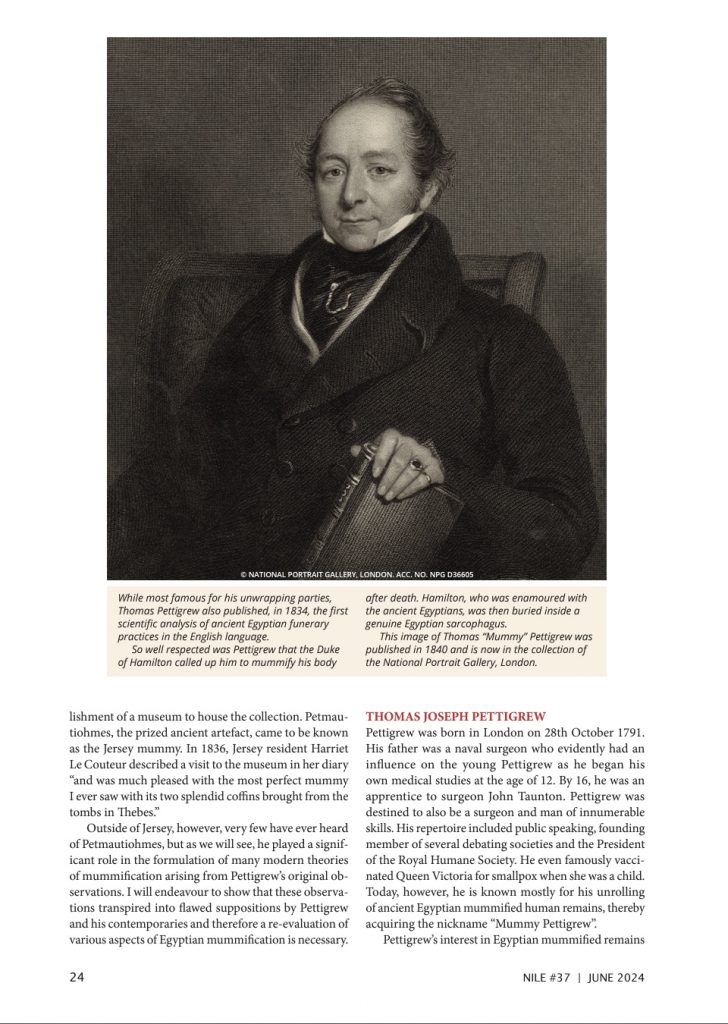

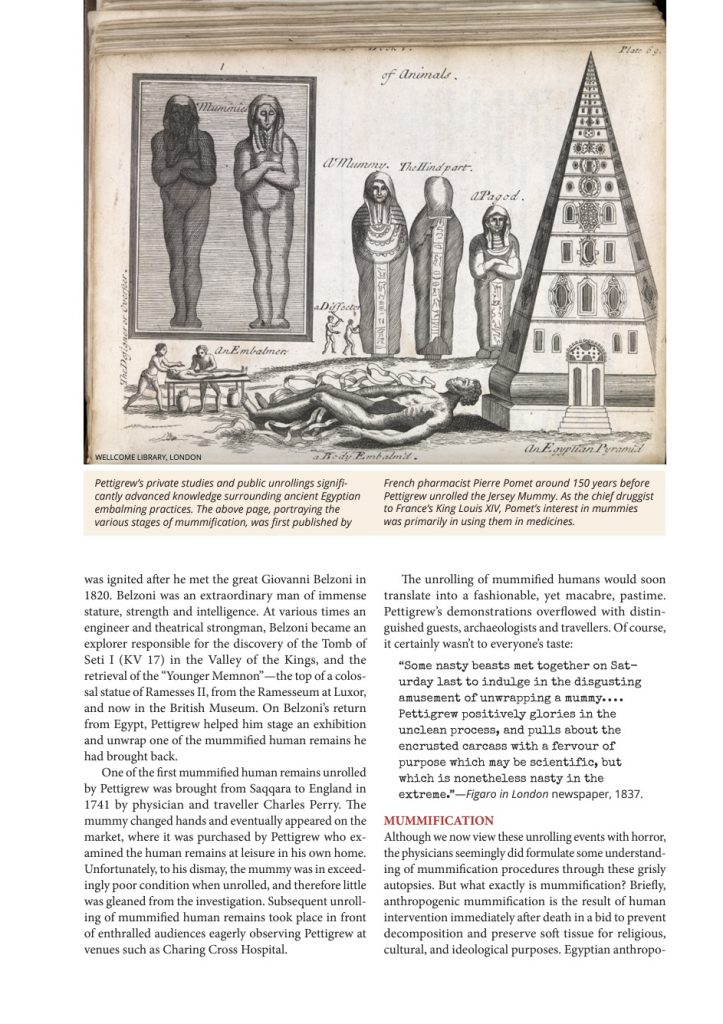

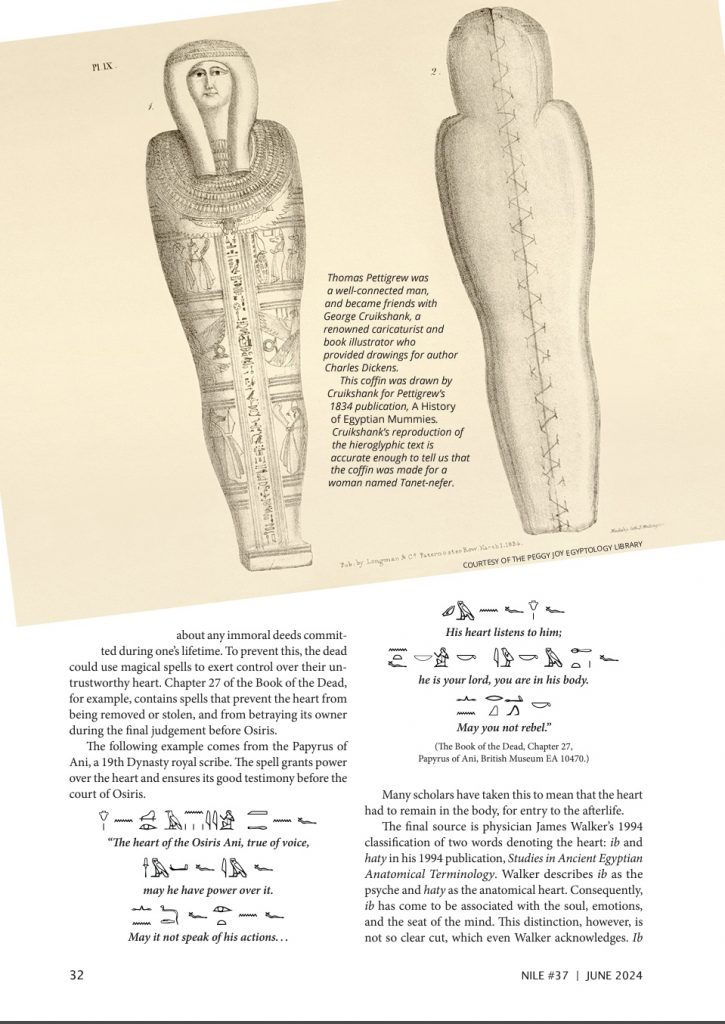

This article presents my research into ancient Egyptian mummification, challenging long-standing assumptions about canopic jars and the role of the Sons of Horus. By re-examining nineteenth-century interpretations alongside textual evidence and modern CT imaging, I argue that these deities protected the entire body cavity rather than specific organs. The findings call for a reassessment of how the ancient Egyptians understood the body, preservation, and the afterlife. A huge thank you to Nile Magazine.

Today Marks 100 Years Since Tutankhamun’s Autopsy Was Carried Out!

International Lounge Podcast

I recently had the pleasure of joining International Lounge Podcast as a guest, alongside my friend filmmaker Curtis Ryan Woodside, for a fascinating conversation about one of ancient Egypt’s most controversial rulers, Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Together we explored not only his revolutionary vision and the glittering city he built at Amarna, but also the darker side of his reign– the suffering endured by those who laboured to create his utopian vision. Our discussion explores the contrast between Akhenaten’s radiant art and worship of the Aten, and the human cost behind his grand experiment.

Listen to the full episode here:

The Missing Heart of Tutankhamun: Unravelling a Modern Mummification Myth

Akhenaten’s Afterlife Documentary

I’m delighted to share that I took part in the new documentary Akhenaten’s Afterlife, produced by my talented friend Curtis Ryan Woodside.

When we think of ancient Egypt, we picture gold, glory and gods. But beneath the radiant sun of Akhenaten’s Amarna lay a very different reality, one carved not in stone but atop fragile bones.

This film peels back the glittering facade of the pharaoh’s “city of light” to reveal a civilisation crumbling under hunger, toil and disease. Excavations of Amarna’s pit-grave cemeteries tell the story of young labourers buried without honour, their bodies marked by brutal work, malnutrition and infection.

At the same time, Akhenaten was rewriting Egypt’s faith, turning away from the gods of his ancestors towards monolatry and devotion to a single deity: the Aten. In doing so, he made himself the only channel between heaven and earth. Was this the result of divine inspiration, political strategy or a troubled, extraordinary mind?

Through science and archaeology, this documentary exposes the haunting truth behind the utopia: a paradise built on human suffering, divine obsession and one of the first recorded instances of power fused with faith.

11th World Congress on Mummy Studies – Cusco 2025

It was an honour to present my research on “The Function and Importance of the Human Brain in Ancient Egypt” at the 11th World Congress on Mummy Studies in Cusco, 2025 (Abstract Below).

Grateful to the organising committee in Peru for their dedication, hospitality and tireless work behind the scenes. Thank you for a truly inspiring conference.

Upcoming Public Lecture

I’m delighted to share that I’ve been invited by the ‘Hapy Egyptology Society’ to give a public lecture on 7th June at 4:15 PM, at ‘The Cooper Gallery’.

In this talk, I’ll present my research, which re-evaluates what ancient Egyptian physicians understood about the brain’s functions, offering fresh insights into their medical knowledge. I’ll also explore new perspectives on mummification methods and ancient Egyptian medicine, shedding light on their remarkable practices.

I hope to see you there!

Egypt’s Unexplained Files

Catch Me Today on Egypt’s Unexplained Files on Sky History

This fascinating series delves into the mysteries of Ancient Egypt, combining cutting-edge science with historical expertise to uncover secrets hidden for millennia. From decoding ancient texts to exploring the lives of pharaohs, the show offers a captivating journey into one of history’s most intriguing civilisations.

Discovery of the Tomb of Thutmose ll

The Great Life of Ramses

I am thrilled to have participated in the 4-part TV series on the life of Ramses ll, a superb production by my talented friend Curtis Ryan Woodside. You can catch it now on Amazon Prime and YouTube!

Ancient Egyptian Dream Charms and Sleep Medicine

This lecture was recorded for Dream Palace Athens 2023.

The Society for the Study of Ancient Egypt

Vital Organs: A Re-evaluation of Ancient Egyptian Mummification

Egypt’s Unexplained Files

Tutankhamun’s Great Grandparents: TUYA & YUYA (FULL DOCUMENTARY)

Manchester Ancient Egypt Society Lecture

A Medical & Historical Re-evaluation of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology in Ancient Egypt

NMEC CAIRO

Coffin of Nedjemankh who was a priest of the god “Heryshaf” at the city of Ahnas. His coffin is made of gilded cartonnage with inlaid eyes and is covered with scenes as well as funerary spells from the Book of the Dead. It dates to the Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BCE).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York repatriated the coffin to Egypt.