I am thrilled to have participated in the 4-part TV series on the life of Ramses ll, a superb production by my talented friend Curtis Ryan Woodside. You can catch it now on Amazon Prime and YouTube!

Ancient Egyptian Dream Charms and Sleep Medicine

This lecture was recorded for Dream Palace Athens 2023.

The Society for the Study of Ancient Egypt

Vital Organs: A Re-evaluation of Ancient Egyptian Mummification

Egypt’s Unexplained Files

Tutankhamun’s Great Grandparents: TUYA & YUYA (FULL DOCUMENTARY)

Manchester Ancient Egypt Society Lecture

A Medical & Historical Re-evaluation of Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology in Ancient Egypt

NMEC CAIRO

Coffin of Nedjemankh who was a priest of the god “Heryshaf” at the city of Ahnas. His coffin is made of gilded cartonnage with inlaid eyes and is covered with scenes as well as funerary spells from the Book of the Dead. It dates to the Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BCE).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York repatriated the coffin to Egypt.

DreamWorks Animation “CURSES” Apple TV

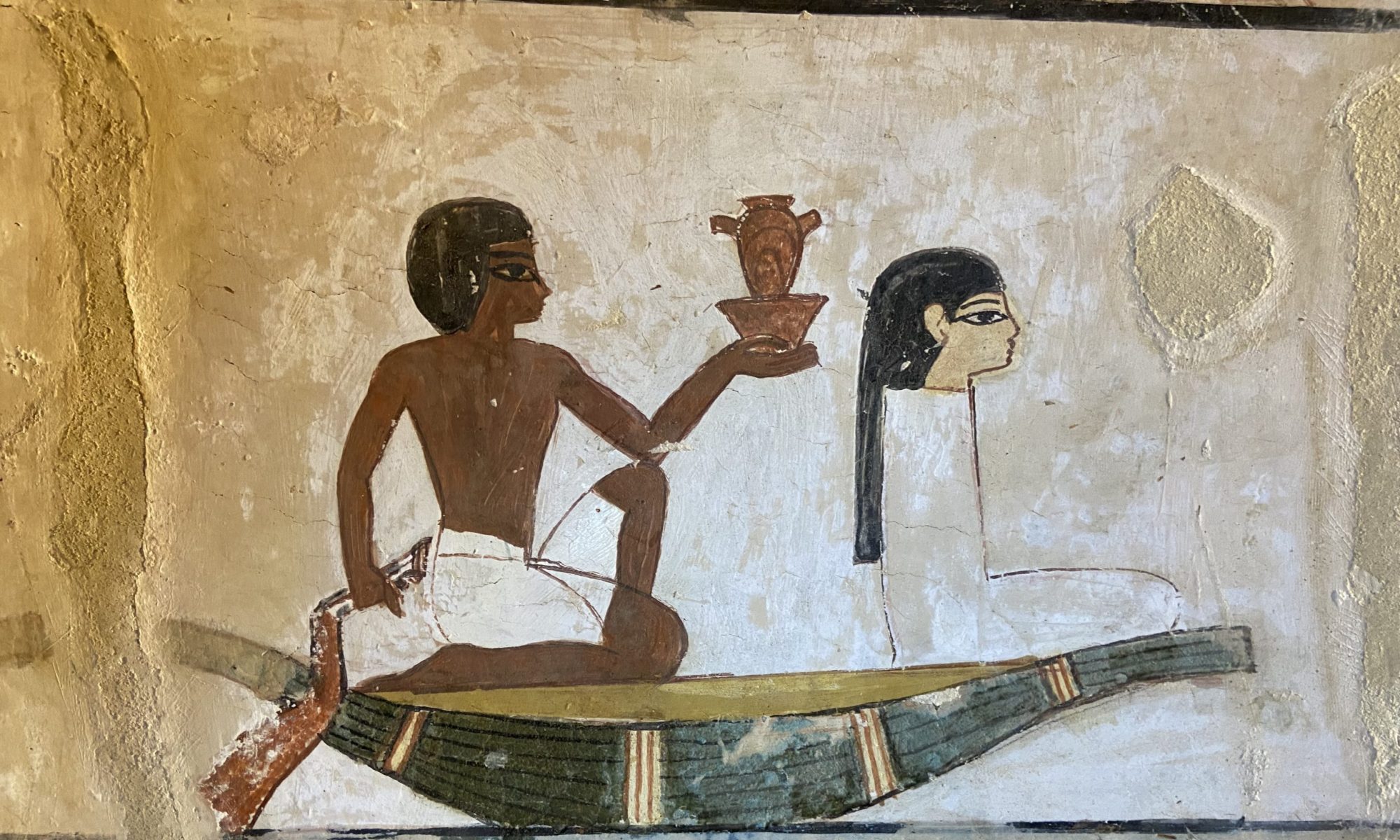

Saqqara 2023

The 13th International Congress of Egyptologists, 2023

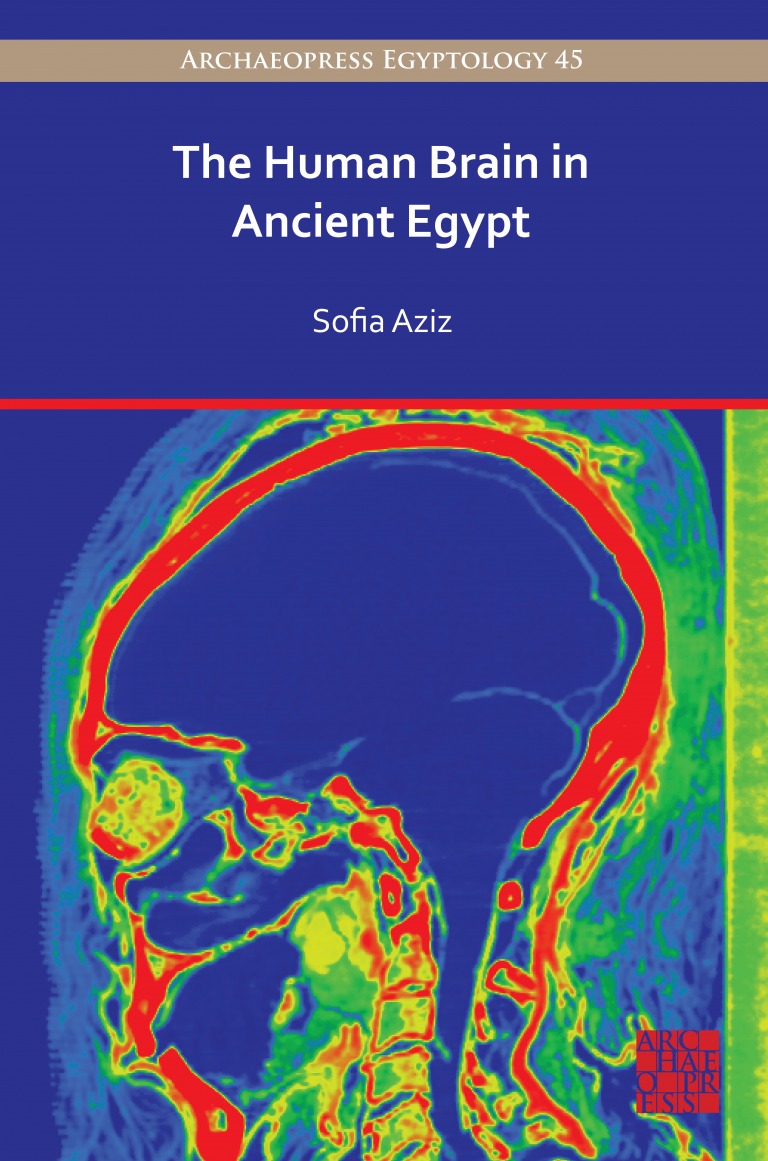

The Human Brain in Ancient Egypt: A Medical and Historical Re-evaluation of Its Function and Importance

The Human Brain in Ancient Egypt provides a medical and historical re-evaluation of the function and importance of the human brain in ancient Egypt. The study evaluates whether treatment of the brain during anthropogenic mummification was linked to medical concepts of the brain. The notion that excerebration was carried out to rid the body of the brain continues to dominate the literature, and the assumption that the functions of the brain were assigned to the heart and therefore the brain was not needed in the afterlife persists. To assess the validity of these claims the study combines three investigations: a radiological survey of 33 subjects using the IMPACT mummy database to determine treatment of the cranium; an examination of the medical papyri for references to the human brain; and an inspection of the palaeopathological records to look for evidence of cranial injuries and ensuing medical treatments.

The results refute long held claims regarding the importance of the human brain in ancient Egypt. Many accepted facets of mummification can no longer hold up to scrutiny. Mummification served a religious ideology in which the deceased was transformed and preserved for eternity. Treatment of the brain was not determined to be significantly different from the visceral organs, and the notion that the brain was extracted because it served no purpose in the afterlife was found to be unsubstantiated.

I am honoured to receive a review of my publication from Dr Sanchez and Dr Meltzer, authors of the exceptional book: “The Edwin Smith Papyrus. Updated Translation of the Trauma Treatise and Modern Medical Commentaries” which was crucial in my research.

A huge thank you to Dr Sanchez for the following review:

“In this work you methodically and strongly and correctly refute the long-held misconception about lack of importance that the brain had for the Ancient Egyptians. Part of this problem has been the unrealistic assumption that our mature concepts of anatomy, physiology and neurology could be uncritically applied to a developing culture of 3000 years + ago. A great achievement of the Egyptian culture was the accumulation and transmission of knowledge that has led to our current structuring of medicine as art and science.

In Chapter 5 you have captured the many clinical “pearls” that demonstrate the Ancient Egyptians’ association of craniocerebral trauma with related high cerebral functions of consciousness, speech, body motion. You have also singled out the very first description by the Ancient Egyptians of the human brain, the cerebrospinal fluid and their accurate physiopathological explanation of the symptom of meningismus.

The histological and molecular analysis of the contents of canopic jars and left over material from embalming caches is an absolute must to ascertain the presence of brain tissue. Perhaps a similar approach can involve studying cranial packing material.“

Gonzalo M. Sanchez M.D. Life Member American Association of Neurological Surgeons.